A 'Dictionary of Musicians' in 1824 - why?

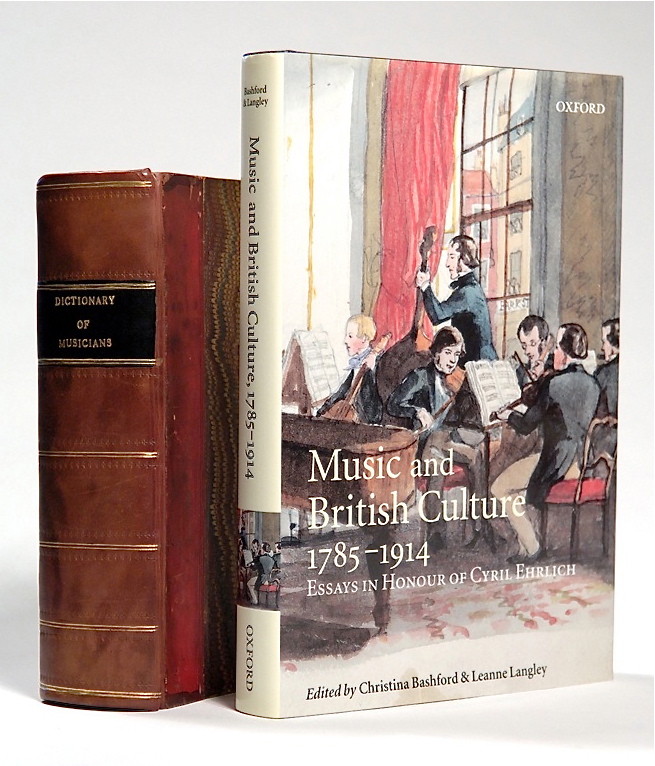

'Sainsbury's Dictionary, the Royal Academy of Music, and the Rhetoric of Patriotism', in Music and British Culture, 1785–1914: Essays in Honour of Cyril Ehrlich, co-edited with Christina Bashford (Oxford: OUP, 2000), 65–97

Music and British Culture, 1785-1914 is a collection of 16 essays by students and colleagues of Prof. Cyril Ehrlich (1925-2004). Ehrlich's pioneering approach to the history of the piano industry and to the British music profession, together with his enthusiasm and generosity, helped reshape the writing of economic and social history in British music studies. This book served as a tribute for his 75th birthday and has remained a solid monument celebrating Cyrilian themes: the growth and articulation of markets, musical taste-shaping, professional training, music and urban identity, concert history, developments in the piano repertory, chamber music and opera, and patterns in audience reception.

'a vast store of new, well-documented information ... refreshingly free of preconceptions and postures'

Nicholas Temperley, Music & Letters

Through a fresh look at old and new sources, my chapter establishes how the nation's first conservatory - the Royal Academy of Music - was founded in 1822 amid a flurry of conflict. In effect, long-established professional plans were sabotaged by the émigré French harpist N.-C. Bochsa, who persuaded George IV and a group of aristocratic amateurs to set up a different kind of institution, with himself, Bochsa, at its head. When the press uncovered Bochsa's role, public subscriptions failed (with no subsidy or serious royal patronage ever being planned).

Bochsa then concocted a book of music biography as an associated vanity project - a Dictionary of Musicians. Its purpose was to fan desire for a conservatory producing 'British' music and musicians, and to draw out nationwide cash in support. Conservatory and dictionary alike were poorly executed, however, full of mistakes. Their intertwined histories and main public operatives, John Fane (Lord Burghersh) and John Sainsbury, shared a fascination with one figure, through Bochsa, that may explain how the Frenchman worked his spell: Napoleon Bonaparte.

You couldn't make this story up - and I didn't. Fortunately, the Royal Academy of Music overcame its troubled beginning, and a better music dictionary was produced sixty years later by George Grove.

'one of the best written, liveliest, pieces in this book, putting forth a really exciting idea'

A Sound Read, BBC Radio 3

'what a marvelous story you narrate ... with verve and brio'

Linda K. Hughes, professor of English literature

The book is available through OUP here. It is also available in dozens of academic libraries worldwide.

Langley

Langley