Joining up the dots

'Joining Up the Dots: Cross-Channel Models in the Shaping of London Orchestral Culture, 1895-1914', in Music and Performance Culture in Nineteenth-Century Britain: Essays in Honour of Nicholas Temperley, ed. Bennett Zon (Farnham: Ashgate, 2012), 37-58

Originally given at the 16th Biennial Conference on 19th-Century Music, University of Southampton, July 2010; revised as 'Invitation to the Dance: Beecham and the Ballets Russes in London, 1911-14' for the Eighth International Biennial Conference on Music in 19th-Century Britain, Queen's University Belfast, July 2011

The explosion in London orchestral culture between 1895 and 1914, so conspicuous to contemporaries, has rarely been studied as a historical phenomenon. Only as ‘concert profusion’ or ‘Edwardian excess’ has the pattern even been noticed, implicating British commerce as an insidious influence. This chapter offers a constructive view of how the struggle to create viable London audiences for serious orchestral music went hand in hand with building professional ensembles – without state or civic subsidy – and how, in turn, more and better listening opportunities educated audiences and stimulated young English composers, including Gustav Holst and Ralph Vaughan Williams.

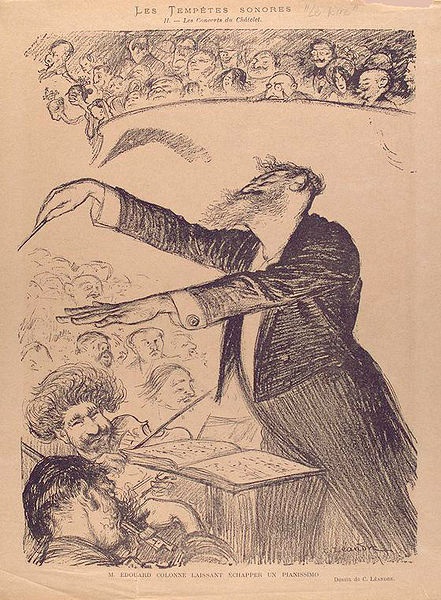

In particular, I argue that Robert Newman’s Queen’s Hall Orchestra (QHO), conducted from 1895 by Henry J. Wood, set a completely new standard of orchestral provision in the English capital, drawing in part on continental practices such as ‘French pitch’, rigorous rehearsal, concerts on Sundays and the entire Lamoureux and Colonne orchestras of Paris as corporate models.

In particular, I argue that Robert Newman’s Queen’s Hall Orchestra (QHO), conducted from 1895 by Henry J. Wood, set a completely new standard of orchestral provision in the English capital, drawing in part on continental practices such as ‘French pitch’, rigorous rehearsal, concerts on Sundays and the entire Lamoureux and Colonne orchestras of Paris as corporate models.

From 1904 several challenges to the perceived QHO monopoly were mounted by ambitious English players, along with younger conductors, in and out of Queen’s Hall. The most audacious of these was Thomas Beecham, who with his father Joseph, their opera company and the Beecham Symphony Orchestra also sought inspiration from across the Channel, not least involving Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes.

Imported French exemplars that stretched players and attracted listeners indeed had a more profound role than is generally understood in modernizing London orchestral capability at this period. In harnessing that energy, Wood and Beecham were more alike than later commentators suggest, just as in absorbing London’s internationalized musical culture before 1915 Holst and Vaughan Williams were more cosmopolitan than conventional nationalist accounts allow.

'Your counterpointing of Wood and Beecham is very rich'

David Wright, social historian of music

'full of good things and very thought-provoking!'

John Lucas, Beecham biographer

This chapter is part of Music and Performance Culture: Essays in Honour of Nicholas Temperley, published by Ashgate in 2012. It is now available from Routledge (Taylor & Francis) here.

Langley

Langley