Making the first 'Grove' music dictionary

'Roots of a Tradition: The First Dictionary of Music and Musicians', in George Grove, Music and Victorian Culture, ed. Michael Musgrave (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003), 168–215

The first edition of Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians was issued by Macmillan & Co. in 25 alphabetical parts between 1878 and 1889. Despite initial problems, it became a publishing phenomenon, then a brand, across the 20th century. The 7th edition, in 29 volumes, appeared in 2001; the 8th is now in progress as Grove Music Online.

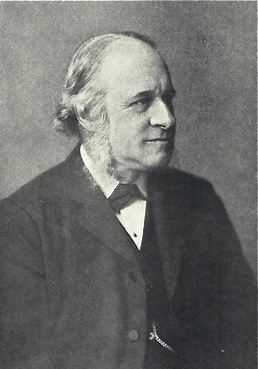

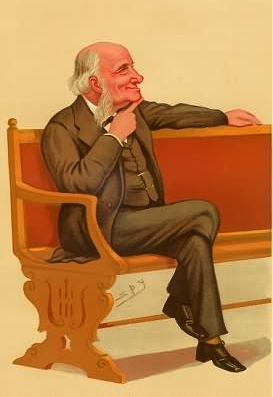

Even before it was finished Grove's dictionary idea transmuted into something the editor never imagined. His name, soon synonymous with the book, accrued an almost religious authority he never sought. Projected to the top of a field in which he always disclaimed his own expertise - he certainly wasn't a musician - he has since become easy prey in revisionist theories about culture formation in the 19th century, and about the value of ‘facts’ in general. Grove was no cultural villain, however; he was a music enthusiast seeking new converts to the pleasures of music. By investigating the Dictionary’s background, execution and reception, this research places both the man and his achievement in truer perspective.

'the gem of the volume … far-reaching, subtle, and imaginative historiography'

Ruth Solie, Music Library Association Notes

Grove’s contracts, his editorial methods, and the printing of the Dictionary fascicles (revealed in ledgers at Oxford University Press) show unsuspected challenges to the project as well as ingenious solutions. Problems of tone and content gave way to those of scope and balance across the alphabet. As new music scholarship, fresh writers and public reaction came through, ‘mission creep’ set in. The editor altered his original concept and lost control.

Yet to his own amazement and that of his skeptical publisher, music scholarship sold books - some 14,000 multi-volume sets by the year 1900. In uncovering the roots of the Grove tradition, this chapter advocates new appreciation not only of modern lexicography, but of the fruitful tension between commerce and music-intellectual work in Victorian Britain.

'positively Schubertian ... makes a warm and compelling case for [the Dictionary's] unique position in our discovery of the musical past'

Nicholas Temperley, Music & Letters

This book is available through Palgrave Macmillan here.

Langley

Langley